Introduction: Where Does Money Come From?

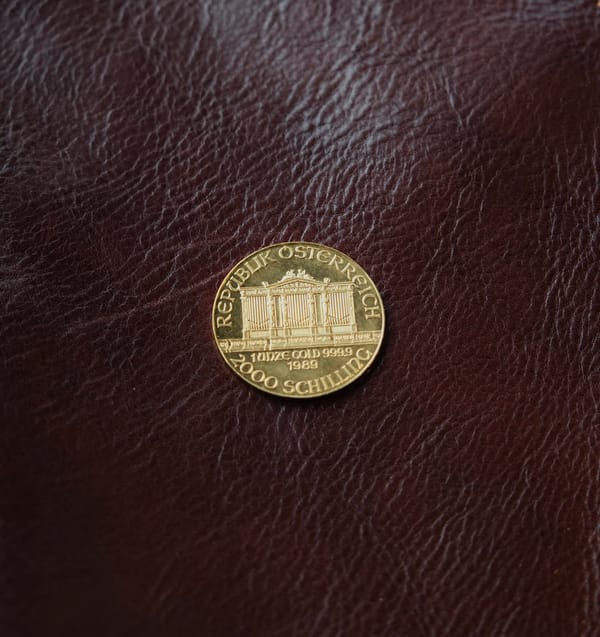

In the previous post I wrote, Why Did the Previous Generation Switch From Gold Standard to FIAT, I explained how money was backed by tangible reserves of gold and how the today's FIAT money system is built entirely on trust, credit, and government backing.

Even the term fiat derives from the Latin word fiat, meaning "let it be done" used in the sense of an order.

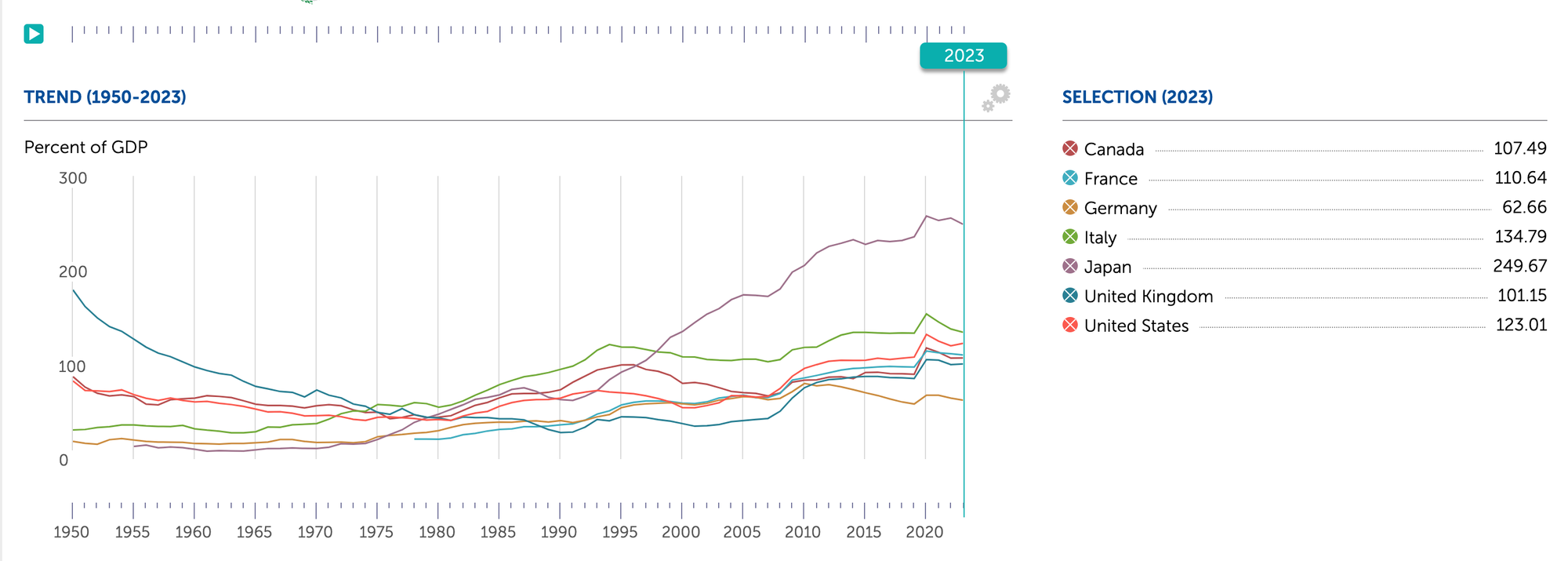

If we check the International Monetary Fund global database for Debt to GDP ratio, we can see the countries with FIAT currencies run on debt:

Economics argue the debt itself isn't bad, as long as it's used for investments. Whenever this is true, a good idea, or sustainable is completely out of question in this article, in which I will focus on HOW the debt is created and dive into the actual techniques used to create new FIAT money:

- How Banks Expand Money Supply With Loans And Factional Reserve Banking

- How Central Bank Lends Money to Governments

1. How Banks Create Money Through Loans

Fractional Reserve Banking: The Engine of Modern Money Creation

When you deposit money into your bank account, it doesn’t just sit there in a vault waiting for you to withdraw it. Instead, banks use a system called fractional reserve banking, which allows them to lend out a portion of your deposit to other borrowers while keeping a fraction in reserve.

If you deposit $1,000, the bank might be required to hold 10% (or $100) in reserve and can lend out the remaining $900 to someone else. This $900 doesn’t come from anywhere—it’s essentially created out of thin air.

When the borrower receives this $900, they might deposit it in their own bank, where 10% is again held in reserve, and $810 is lent out to another borrower. This process repeats, creating multiple layers of loans and deposits. What started as a $1,000 deposit can multiply into $10,000 in total money supply, depending on the reserve requirement. This is why fractional reserve banking is often referred to as money creation through lending.

In this system, money is created by issuing loans. Banks change digital balances in borrowers' accounts. These balances act as new money in the economy, fueling spending, investment, and economic growth.

Credit as a Form of Money

It’s crucial to understand that most of the money circulating in modern economies isn’t cash but credit. Loans like mortgages, car loans, and business loans are forms of credit that act as money. When a bank approves a $200,000 mortgage, it doesn’t move $200,000 in physical cash to the borrower’s account. Instead, it creates a digital balance that the borrower can use to purchase a home. This digital balance is treated as money, even though it’s essentially an IOU (I owe you).

The modern economy thrives on this system of credit creation. Borrowing allows businesses to invest in new projects, consumers to purchase homes and cars, and governments to fund infrastructure. However, it also means that most of the money we use is tied to debt. For every dollar created, there is a corresponding obligation to repay it, with interest.

The Role of Trust in the Banking System

Fractional reserve banking works because of one key assumption: not everyone will withdraw their money at the same time. Banks operate on trust—trust that depositors won’t all rush to withdraw their money, and trust that borrowers will repay their loans. This trust is what keeps the system running smoothly. However, if trust collapses—such as during financial crises—banks can face bank runs, where depositors demand their money all at once, forcing banks to close their doors. This happened during the Great Depression and, more recently, during the 2008 financial crisis.

Governments and central banks play a critical role in maintaining this trust. They regulate banks, insure deposits, and act as lenders of last resort to prevent bank failures. But trust is fragile and citizens are becoming skeptical of institutions.

2. How Central Bank Lends Money to Governments

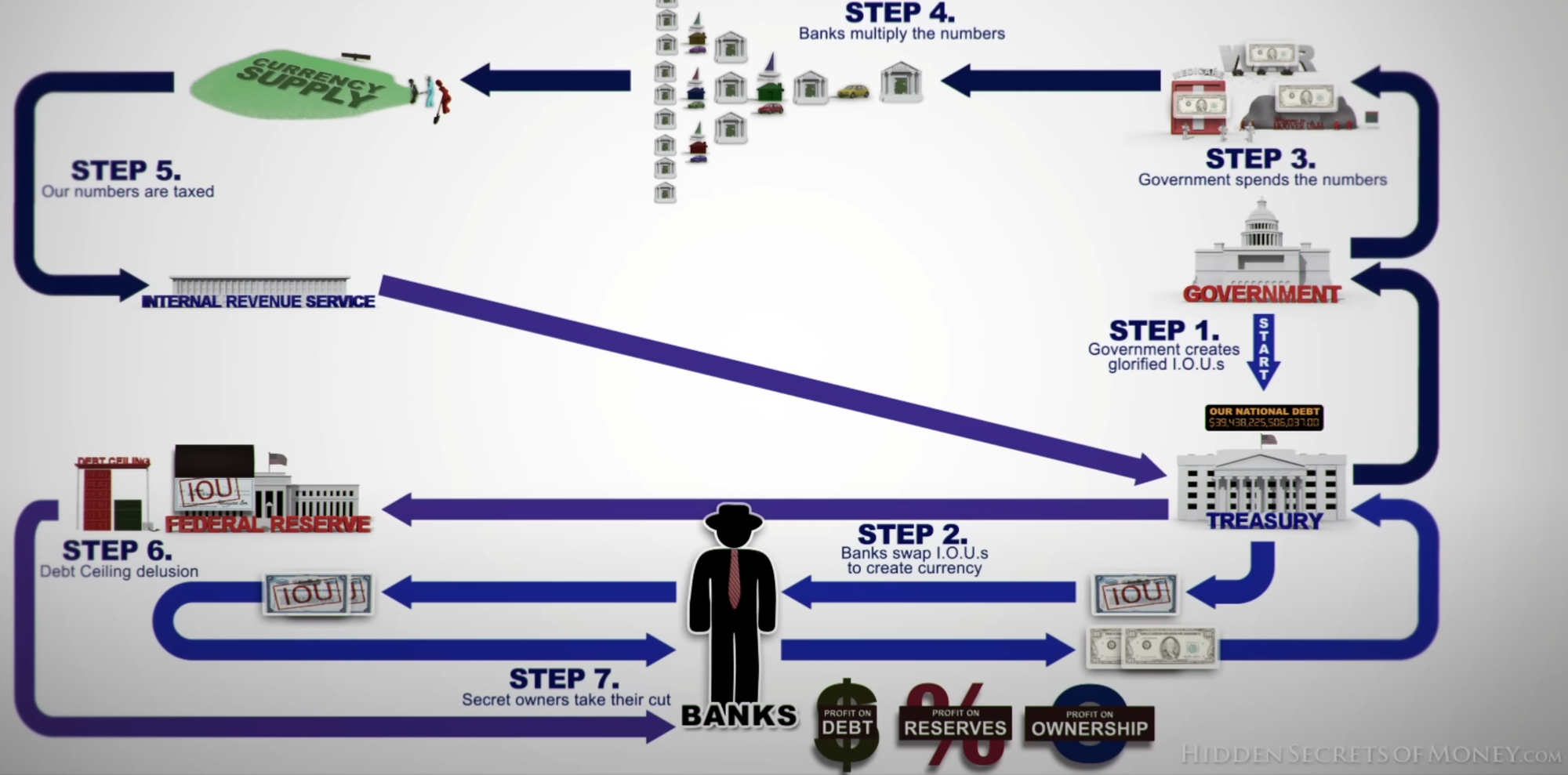

Step 1: Government Needs Money

Governments often spend more than they collect in taxes, creating a budget deficit. To fill this gap, they borrow money by issuing government bonds. These bonds are essentially IOUs, where the government promises to repay the bondholder a fixed amount (the face value of the bond) with interest at a later date.

Think of it like this:

- The government says, “I need money now, so I’ll sell you a bond. If you buy it, I’ll pay you back with interest in the future.”

Step 2: Who Buys the Bonds?

The government sells these bonds to a range of buyers, including:

- Commercial Banks: Banks use their reserves or customer deposits to buy bonds as a way to earn a safe return. Bonds are a reliable investment for banks.

- Other Investors: Pension funds, insurance companies, private investors, and even foreign governments often buy bonds.

- Central Banks: Central banks can also step in and purchase government bonds, but they do so in a unique way that involves creating new money.

Step 3: Central Banks Monetize Debt

The central bank’s role is special because, unlike commercial banks or investors, it can literally create new money to buy government bonds. Here’s how it works in two main scenarios:

Scenario 1: Central Bank Buys Bonds Directly

This is relatively rare because in most developed economies, central banks are designed to operate independently of their governments to ensure monetary policy decisions are free from political influence. Directly buying bonds from the government could blur the lines between fiscal and monetary policy, but it does happen and it works like this:

- Government Issues Bonds: The government needs $1 billion, so it issues $1 billion in bonds.

- Central Bank Buys the Bonds: The central bank directly purchases these bonds from the government.

- Money Creation: The central bank doesn’t need deposits or reserves to do this—it simply credits the government’s account at the central bank $1 billion. This newly created money can then be spent by the government on public services, salaries, infrastructure, or welfare programs.

This is called debt monetization because the central bank is turning government debt (the bonds) into money circulating in the economy.

Scenario 2: Central Bank Buys Bonds Indirectly via Open Market Operations

This is the more common method used by central banks, and it involves secondary markets:

- Government Issues Bonds: Just like before, the government sells $1 billion worth of bonds to raise money. However, in this case, commercial banks, financial institutions, or investors are the ones who initially buy these bonds.

- Central Bank Enters the Secondary Market: After the bonds are sold to private buyers, the central bank can step in and buy these bonds from the banks or investors on the open market. The central bank pays for the bonds by crediting the seller’s account with newly created money. This process injects new money into the banking system.

I know what you are thinking. The key result from Scenario 1 (central bank buying bonds from government) and Scenario 2 (central bank buying bonds from the commercial banks) seem the same - why doesn't the central bank just directly purchases the bonds from government, skipping the commercial banks?

Central Bank Independence: A Practical Illusion?

Central bank independence is less about being fully insulated from government needs and more about creating a framework that appears to separate monetary policy (managing inflation, money supply, and interest rates) from fiscal policy (government taxation, spending, and borrowing).

Given that the central bank can eventually buy bonds in the secondary market, why go through this roundabout process? The answer lies in perception, control, and market dynamics:

Buffer

The use of secondary markets creates a layer of separation between the central bank and the government. Here’s why this matters:

- Market Discipline: In the secondary market, the government first sells bonds to private investors, including banks, pension funds, and individuals. This process forces the government to compete for financing and accept interest rates determined by the market, reflecting the perceived risk of its debt. This acts as a check on excessive borrowing because higher debt levels usually mean higher interest rates for new borrowing.

- Central Bank's Role: The central bank enters the market later to stabilize financial conditions or manage liquidity—not explicitly to fund the government. It can justify its actions as necessary for managing the money supply, interest rates, or economic growth, rather than directly supporting government spending.

If the central bank were to bypass this process and buy bonds directly from the government, it removes this market discipline entirely and raises concerns that governments could abuse the central bank’s money-printing power for unchecked deficit spending.

Legal and Historical Constraints

Most countries legally prevent their central banks from directly financing government debt with rare exceptions during crises like wars or pandemics.

These rules were put in place precisely to avoid the pitfalls of overt monetary financing, which has historically led to hyperinflation and loss of confidence in the currency like in Weimar Germany in the 1920s.

The U.S. Federal Reserve Act actually prohibits the Federal Reserve from directly purchasing U.S. Treasury securities at auction. And the European Central Bank (ECB) is also explicitly forbidden from directly financing EU governments under the Maastricht Treaty.

Allowing Market Price Discovery

When the government issues bonds to private investors first, the market determines the interest rate (yield) based on supply and demand. This ensures that bond prices reflect the government's creditworthiness and broader economic conditions. If the central bank were the sole buyer, there would be no true price discovery, and the government could set artificially low interest rates on its debt.

Managing Liquidity

By buying bonds from banks, the central bank injects reserves into the banking system, enabling banks to lend more and stimulate the economy, and the timing and scale of bond purchases can be adjusted based on economic needs, giving the central bank greater flexibility to manage inflation, unemployment, and growth.

Is Central Bank Independence Real?

Critics often argue that central bank independence is largely a myth because central banks inevitably support government borrowing in one way or another. Here’s why:

- Governments are often the largest issuers of bonds, so central banks frequently buy government debt as part of their regular operations, whether directly or indirectly.

- Central banks also have strong incentives to keep interest rates low to prevent excessive debt servicing costs for governments. This creates a conflict of interest, as raising interest rates to combat inflation could destabilize government budgets.

- During crises (e.g., COVID-19, 2008 financial crisis), central banks often abandon pretense altogether and engage in large-scale asset purchases (quantitative easing), which directly or indirectly finance government deficits.

While central banks strive to maintain the appearance of independence, their actions are often closely aligned with government needs, especially during periods of high debt or economic instability.

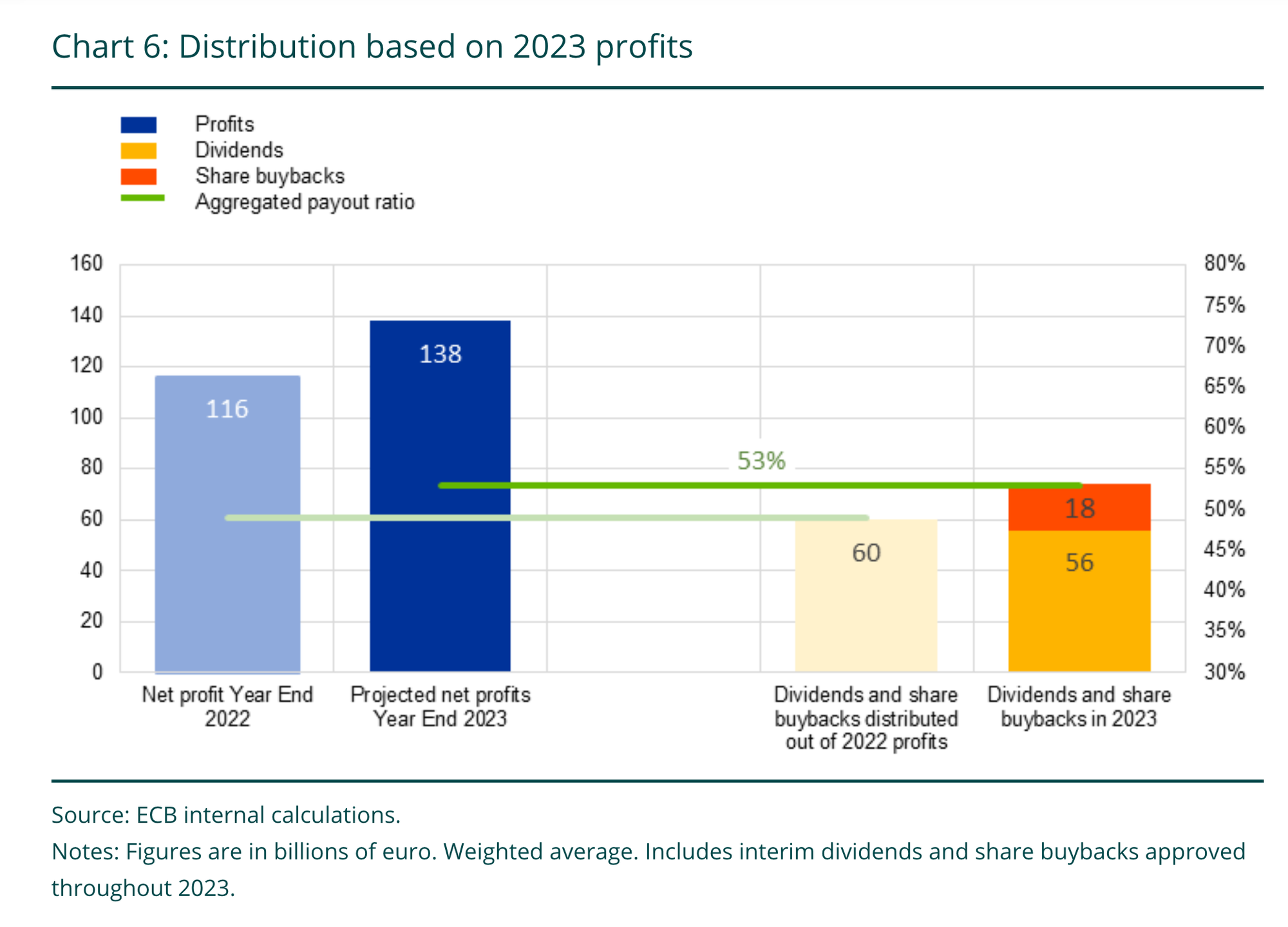

Bailout for Banks, Funding Governments, Wars and Pandemics in 2024

To bring in real numbers, in March 2020 the ECB launched a temporary bond-buying program called The Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) designed specifically to combat the economic impact of COVID-19. As a result, the ECB injected €1.85 trillion of new money into the economy.

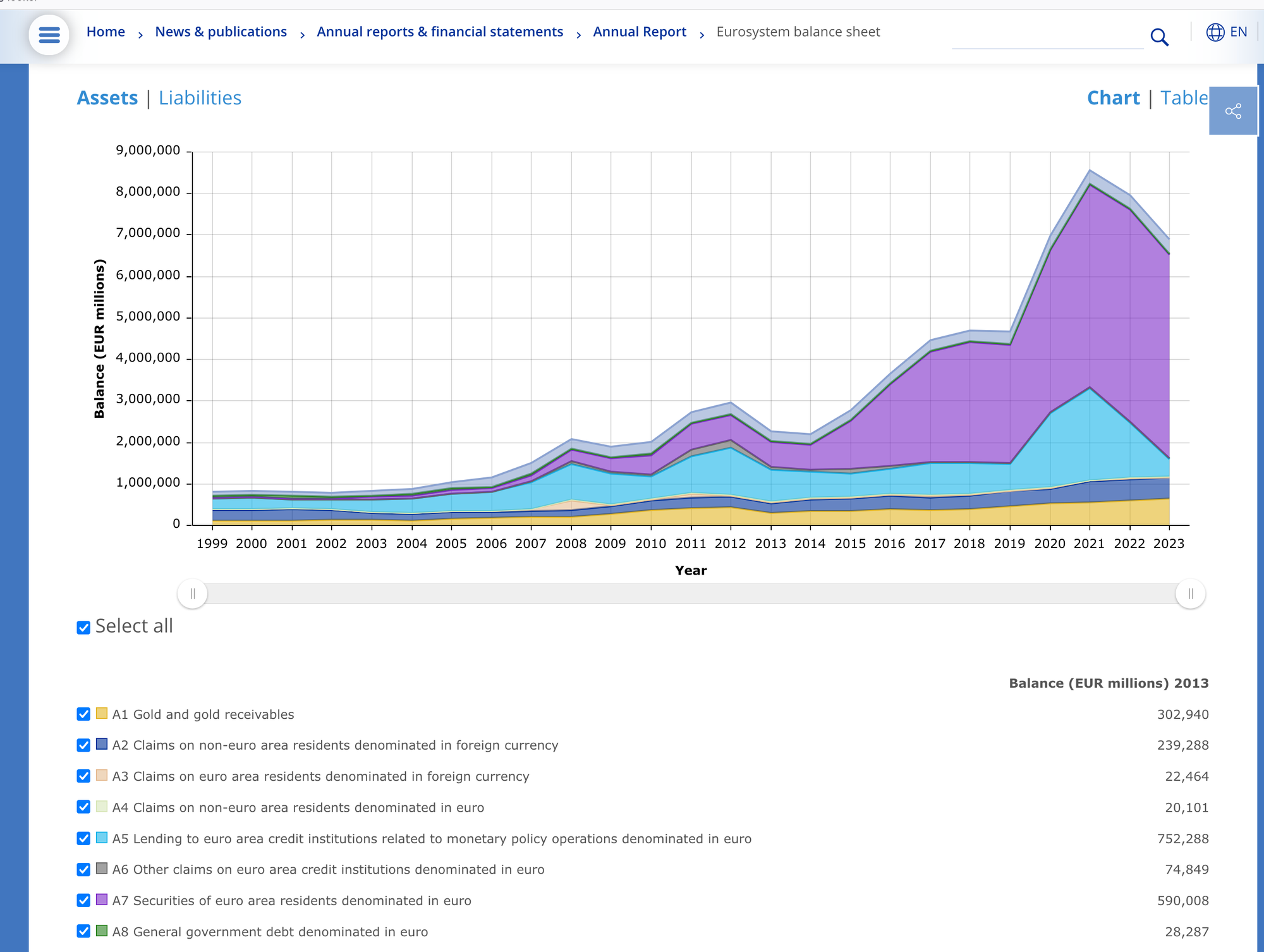

Zooming out, the ECB's balance sheet expanded significantly from around €600 billion in 1999 to approximately €8.8 trillion by mid-2022 — an approximately 14-fold increase over this period.

Source:

How Banks Profit

Expanding the money supply through loans and government debt may stimulate economic growth, but it doesn’t happen without a cost. A key beneficiary of this system is the banking sector itself, which profits at nearly every stage of the process. While central banks play their role in managing the broader economy, commercial banks have strong financial incentives to maximize lending, increasing their profits while indirectly passing costs on to citizens.

Here is a list of a few banking instruments to grow revenue:

- Loan Origination Fees: When banks issue loans, they typically charge origination or administrative fees. These fees alone generate billions of dollars annually for banks. The more money banks lend, the more they profit.

- Interest Income: Banks profit from the difference between the interest rate they pay on deposits and the higher rate they charge on loans (the net interest margin). As loans make up the majority of new money creation, this process funnels vast amounts of wealth to the banking sector.

- Bond Market Profits: When banks buy government bonds, they not only earn interest but also benefit from the stability and safety provided by government backing. In many cases, these returns are virtually risk-free because central banks stand ready to purchase bonds in case liquidity is needed. This creates a system where banks profit from lending to governments, often at the expense of taxpayers.

- Fees on Money Transfers: Banks collect fees for handling money transfers between governments, businesses, and citizens. Whether it’s bond transactions, debt refinancing, or even regular customer banking, banks profit from being intermediaries in the flow of money.

The result is a system of regulatory capture, where banks, as key players in the financial system, profit at every turn while citizens without assets, or lacking financial intelligence bear the long-term consequences of reduced purchasing power, must borrow to purchase inflated assets, face high progressive taxes as a result of climbing the inflation-inflated tax brackets while trying to outrun the system as they chase the next salary increase.

The euro has lost 50% of its purchasing power over the last 20 years. When was the last time your country's government adjusted the tax brackets for inflation?

Conclusion: Who Should Control Money Creation?

The process of creating money through lending has traditionally been the responsibility of banks, supported by governments and central banks. This system has fueled economic growth for a century but not without consequences.

If I, as an European Citizen in 2025, want to borrow 300 000€ to purchase my first inflated flat in a small Slovak town from a commercial bank at 3.99% interest, in 30 years the total sum I will pay to the bank is 596 779€.

I have no other option but to take a loan from a bank.

Or do I?

Why should the creation of money—one of the most fundamental components of our financial system—remain solely in the hands of banks?

With the rise of blockchain technology and decentralized finance (DeFi), we now have an alternative model. Imagine a world where the creation of money is governed by transparent and predictable algorithms. A system where peer-to-peer (citizen-to-citizen) protocols offer lending and borrowing mechanisms that operate openly, with pre-programmed rules and without favoring the interests of any centralized entity. Protocol where citizens can directly vote on interest changes, fractional reserve ratio, lending requirements and other components as members of the protocol's DAO (decentralized autonomous organization).

Could decentralized, permissionless systems create a more open, transparent, predictable and efficient allocations of capital?