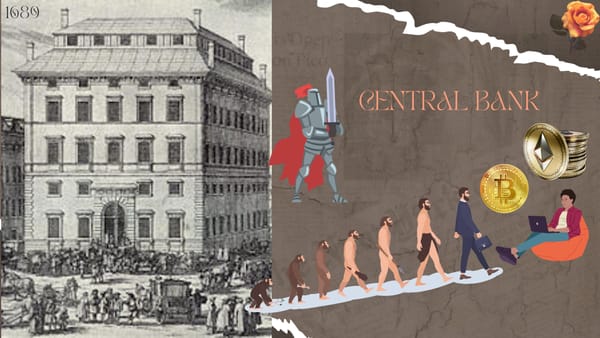

Before we start reverse-engineering Web3 codebases together, let's traverse through the history and learn about money and what monetary systems led to the 21st-century cryptocurrencies.

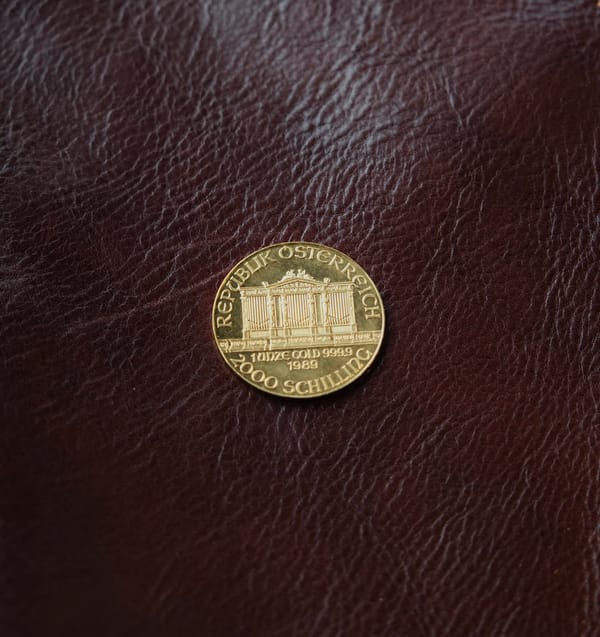

You are in the 7th century BCE in Lydia, present-day Turkey. A breeze of innovation sweeps the land, and you're at the inception of a revolutionary monetary system — the birth of the first standardized gold coin by the Lydians.

Athens embrace the coinage revolution and kickstart a period of prosperity, an epitome of intellectual enthusiasm and flourishing commerce. Here, the Lydian coins meld seamlessly into the thriving Athenian economic ecosystem. This groundbreaking innovation reshapes economic transactions, offering a newfound fluidity in trade and commerce. The Drachma, a silver coin, emerges as the standard currency, embodying the financial vigor of Athens to perform day-to-day trade, while gold coins are used to settle more expensive transactions.

The Drachma, in its pristine state, serves as a reliable metric of value. A skilled worker or a hoplite in Athens would typically earn approximately one Drachma per day, translating the daily sweat and toil into tangible, valued silver and enough for the daily subsistence of a family of three. This coin, bearing the symbolic owl of Athens, manifests the economic pulse of the city, underlining the labor and service value within the Athenian polity.

Silver and gold become both a currency and money.

Currency:

- medium of exchange

- a unit of account

- portable

- durable

- divisible

- fungible

Money:

- currency

- store of value

Athenian coinage was especially attractive internationally due to the purity of the silver used to create each coin.

After decades of prosperity, Athens enter a tumultuous period by engaging in the arduous Peloponnesian War with Sparta, which lasted from 431 to 404 BC, a conflict that strains the city's resources and necessitates heightened military expenditure. The government, hidden behind the grandeur of democracy, quietly commences the debasement of its cherished Drachma by mingling the noble silver with base copper, crafting a purposefully diluted alloy. The greedy debasement of currency becomes a means for Athens to finance the war without depleting its precious silver and gold reserves and to facilitate state-funded projects to sustain the city through the long-drawn conflict.

The repercussions of weakening currency by the government's decision to artificially expand the amount of coins in circulation disproportionally to the bank's silver and gold reserves are felt by each worker and hoplite in Athens. The government's intrusion brings a wave of uncertainty to every hard-earned Drachma.

This unfolding scenario reveals the tense dance between individual worth and state interference. Through the tale of Athens and its diminished Drachma, enduring insights emerge about the continuous struggle between government maneuvers and citizens' wealth.